Literature Review Part 1: Why does the United States based conservation community care about equity in conservation?

The purpose of the literature review is to establish the current state of knowledge on a particular topic, identify gaps in the existing research, and highlight areas where further research is needed

“Why does equity in conservation matter to you?”

A view of the Chicago River in the heart of downtown Chicago

What is conservation?

Before digging into why equity matters in conservation, let’s start with defining ‘conservation’. How do you define it?? Pre-2020, my personal definition of conservation emphasized the protection of beautiful places for recreation with a focus on sustainable natural resources management. This is seen in an interview I provided in 2011, while working for the Conservation Corps of Minnesota and Iowa. So young with so much to learn 🙂

A quick google search quickly brings up pages and pages of organizations, individuals, and governments speaking to conservation. Their language varies in complexity, level of depth, and emphasis on biodiversity and people.

I am keen on the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute’s definition in the video below, which equates conservation to ‘no harm’. Who defines harm? What has led us to this moment and how does it relate to equity?

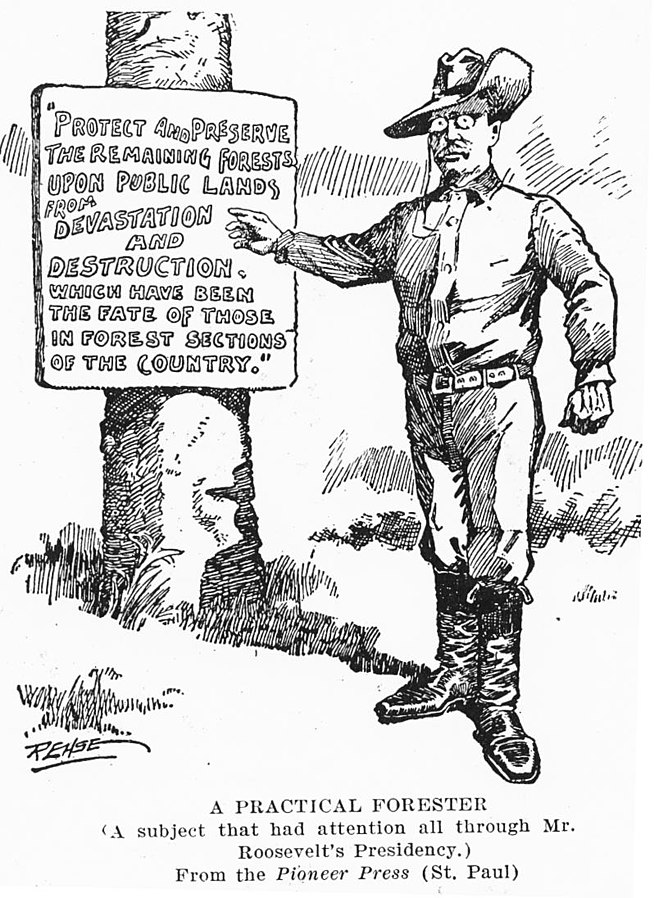

Timeline of U.S. Conservation History12

Our collective appreciation and definition has evolved over the last 200 years with a significant change beginning in 1850. What was happening in the U.S. in the 1850s that moved the nation from ‘Wilderness and Abundance’ to ‘Depletion of Natural Resources’?. After the U.S. Civil War ended in 1865, the United States expanded its railroads. Additionally, it pushed industrial petroleum refining, steeling manufacturing and electric power to new heights of prosperity. 3 With expanded markets and access to wealth, even the remotest parts of the country were up for grabs. And ever since then, conservation strategies and framings continued to evolve (Mace, 2014)4.

The National Park Service breaks this evolution into six phases:

- Prior to 1850: Wilderness and Abundance

- 1850 – 1900: Depletion of Natural Resources

- 1900-1932: Regulation and Preservation

- 1933 -1961: Resource Management

- 1962-1980: Environmental Concern

- 1981 to Now: Global Environment and Sustainable Development

Dr. Georgina Mace’s 2014 Science Journal publication ‘Whose Conservation?’ focuses on four stages starting with the 1960s (Give this a read, Dr. Mace is amazing)

- 1960s – 1970s: Nature for Itself

- 1980s – 1990s: Nature Despite People

- Early 2000s: Nature for People

- Modern Day: People and Nature

- TBD – Conservation for Whom?

What’s missing in this list?

The lists above provides neatly laid out evolution for environmental conservation. However, what I don’t see reflected is the irreversible and negatives impacts to many of our precious plants, animals, waterways, soils, vistas, and people. RIP Passenger Pigeon. Words like depletion sound gentler than the reality, such the Johnstown, PA flood in 1889 that killed thousands of people. Here’s more about it as written by Robert McNamara5:

“The city of Johnstown, a thriving community of working people in western Pennsylvania, was virtually destroyed when a massive wall of water came rushing down a valley on a Sunday afternoon. Thousands were killed in the flood.

The entire episode, it turned out, could have been avoided. The flood occurred after a very rainy spring, but what really caused the disaster was the collapse of a flimsy dam built so that wealthy steel magnates could enjoy a private lake. The Johnstown Flood wasn’t just a tragedy, it was a scandal of the Gilded Age.“

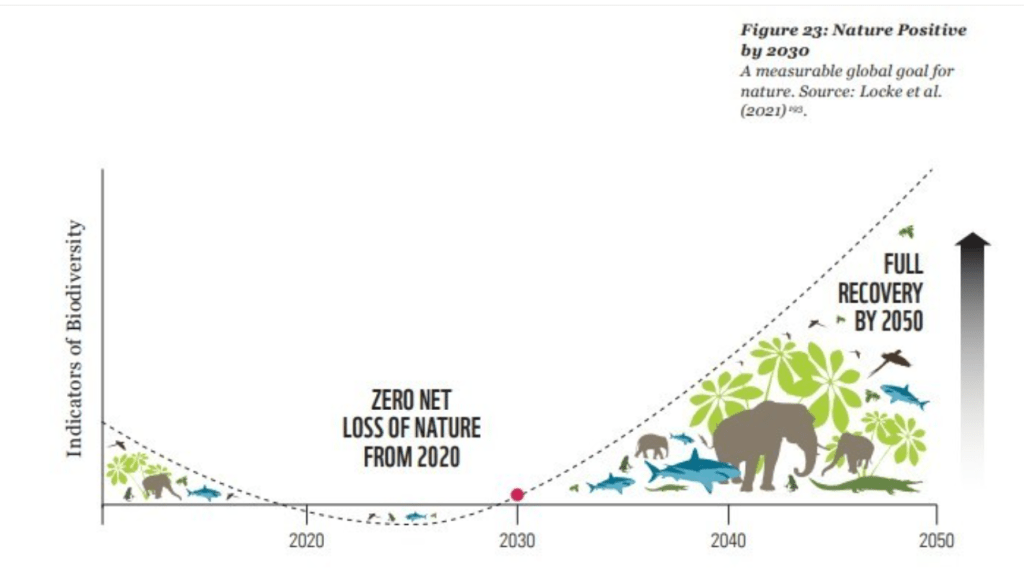

This might feel like ancient history, but climate change impacts (IPCC, 2022)6 and continued devastating loss of birds, bees, blossoms, and all of the species that call our planet home (Dasgupta, 2021)7 coupled with social challenges from rising inequality (Hamann et al., 20188; Piketty, 20209) continue to pose critical threats to communities. Those with lower socio-economic standing will suffer disproportionate impacts (Diffenbaugh & Burke, 201910) and this moment calls for a rapid need to evolve thinking around conservation. Let’s not repeat the Johnstown Flood.

Early principles of conservation: a history of privilege and power

Curiously enough, the individual is usually so deeply immersed in his culture that he is scarcely aware of it as a shaping force in his life. As someone has remarked, “The fish will be the last to discover water.” 1112

When reflecting on my nearly two decade obsession with all things environmental conservation, I quickly see that I AM the fish. Frankly, I believe many folks in this field are swimming around without a clear sense of its origin story. As well as the long-held beliefs and social constructs that define good conservation. Reading Dorceta E. Taylor’s 2016 work, ‘The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power Privilege, and Environmental Protection’13, challenged assumptions and long-held beliefs I’ve held and underestimated. Her research serves as deep inspiration for this blog post. Dorceta focuses on how dominant world views and colonialism contribute to the foundation and values around conservation. The book is over 400 pages and well-worth the read, even if it takes you six months like me!

Taylor shares stories about the impacts of ‘fortress conservation’, which assumes protecting bio-diversity means carving out isolated places where people’s presence is incompatible14….. even forcibly removing Native peoples who lived in harmony with the land for centuries15. And tales of communities losing access to hunting and fishing grounds, where subsistence harvesting came into conflict with the recreational desires for the well-to-do. As well, as celebration for notable people of color and women that found a way to be heard in the midst of so much environmental unraveling. She shines a light on a history we need to know in order to move forward towards a more inclusive and sustainable future for our planet. The next chapter for conservation requires us to challenge what we know and think more deeply about whose voice and well being isn’t in the room.

But hasn’t there been some good in the last 200 years?

Absolutely!! If it wasn’t for the work of thousands of caring professionals, volunteers, and donors over all of these years, the Earth would be in even worse shape! We have lands and waters that are accessible for all and in some cases the haven for species on the verge of disappearance. However, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), since 1970, our wildlife populations have dropped by 69%. 16 This is a tremendous loss and I truly believe we can work together in better ways to reach positive outcomes for all species, humans included.

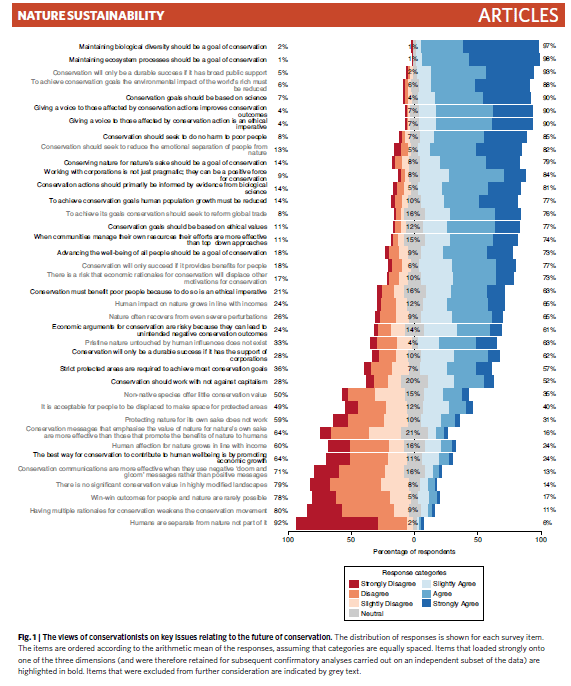

Values and Definitions are Changing

I have a lot of grace and curiosity about how my younger self thought about the world and the work that still motivates me. Additionally, I extend these sentiments to anyone interested, living, volunteering, and/or working in this space. The way people define this work is nuanced, especially around the intrinsic value of ‘nature’ (not my favorite word, hence the air quotes), the role of humans in its management, and the level of extraction for human consumption. This is demonstrated in research started around 2017 by a consortium of European Universities, including Cambridge University. The Future of Conservation17 study, with over 20,000 participants worldwide, shows the diversity and range of thoughts on key values in conservation. As well as how ideologies around ‘traditional’ and ‘new’ conservation are playing out across the world. Nonetheless, even though many of the origins of conservation were established by those with power…. the future of this conversation is changing.

References

- https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/nineteenth-century-trends-in-american-conservation.htm ↩︎

- https://www.slideserve.com/mayes/a-history-of-wildlife-conservation-what-have-we-learned-in-150-years ↩︎

- https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/overview/ ↩︎

- Mace, G. M. (2014). Whose conservation? Science, 345(6204), 1558–1560. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1254704

↩︎ - McNamara, Robert. “Great Disasters of the 19th Century.” ThoughtCo, Apr. 22, 2025, thoughtco.com/great-disasters-of-the-19th-century-1774045. ↩︎

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844. ↩︎

- Dasgupta, P. (2021), The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. Full Report. 610 pages. (London: HM Treasury) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/final-report-the-economics-of-biodiversity-the-dasgupta-review ↩︎

- Hamann, M., Berry, K., Chaigneau, T., Curry, T., Heilmayr, R., Henriksson, P. J. G., Hentati-Sundberg, J., Jina, A., Lindkvist, E., Lopez-Maldonado, Y., Nieminen, E., Piaggio, M., Qiu, J., Rocha, J. C., Schill, C., Shepon, A., Tilman, A. R., van den Bijgaart, I., & Wu, T. (2018). Inequality and the Biosphere. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(1), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025949

↩︎ - Piketty, T., & Goldhammer, A. (2020). Capital and ideology. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

↩︎ - Diffenbaugh, N. S., & Burke, M. (2019). Global warming has increased global economic inequality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(20), 9808–9813. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816020116

↩︎ - 1960, Personality Dynamics and Effective Behavior by James C. Coleman, Including Selected readings prepared by Alvin Marks, Quote Page 59, Column 2, Scott, Foresman and Company, Chicago, Illinois. (Verified with scans) ↩︎

- https://mcluhangalaxy.wordpress.com/2014/02/02/we-dont-know-who-discovered-water-but-we-know-it-wasnt-a-fish ↩︎

- Dorceta E. Taylor. The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2016 . ↩︎

- https://sesmad.dartmouth.edu/theories/85#:~:text=Fortress%2C%20or%20protectionist%2C%20conservation%20assumes,biodiversity%20loss%20and%20environmental%20degradation. ↩︎

- https://www.intermountainhistories.org/tours/show/30 ↩︎

- https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/10/nature-loss-biodiversity-wwf/ ↩︎

- Luque‐lora, R, Keane, A, Fisher, JA, Holmes, G & Sandbrook, C 2022, ‘A global analysis of factors predicting conservationists’ values’, People and Nature, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 1339-1351. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10391 ↩︎

Leave a comment